Dr. Barraud House Trash Pit

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1713

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

2010

Dr. Barraud House Trash Pit

Principal Investigator

Marley R. Brown III

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Archaeological Research

Fall 1987

Re-issued

April 2001

Dr. Barraud House Archaeological Report

Archaeological investigations have been conducted twice by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation on the Dr. Barraud property, in an effort to locate the remains of colonial period outbuildings and other features. Significant archaeological informatio was revealed in both excavations.

1941 Archaeological Investigations

When the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation acquired the Barraud lot, located at the northwest corner of Botetourt and Francis Streets, the residents of the property were already aware of the archaeological features existing on their lot. Mrs. Ryland, the life tenant of the house, discussed "the general location of foundations she had touched while gardening", but the exact placement of this brickwork was never recorded (memo 8/6/41). During general yard work throughout the years, Mr. Ryland had also noticed "considerable remains of brickwork north of a standing outbuilding". It was first suggested in early 1940 that these remains be investigated archaeologically by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Funding to begin archaeology on the Barraud lot was authorized in June of 1941, and the excavations were reportedly conducted between the summer and early fall of that year. To clear the way for this work, a standing outbuilding on Botetourt street was demolished, as well as parts of the Barraud House dismantled.

The archaeological investigations were supervised by James M. Knight, architectural draftsperson and archaeologist for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation from 1936 to the early 1960s. Some of the lot was examined by a method known as cross-trenching. This technique, consisted of digging trenches spaced 5' to 10' apart, across the lot at a 45 degree angle to the colonial street lines. By excavating these trenches down to the sterile yellow clay layer (located at a depth of approximately 2'), buildings with continuous brick foundations could be located expediently. Other portions of the Barraud lot were stripped of soil to expose overlapping brick foundations present there. Foundation walls were uncovered, excavated down to the bottom course of brickwork, and in some instances, the entire interiors of the structures were excavated. At this point, the building remains were photographed, mapped, and dated based on factors such as dimensions, brick size and color, mortar composition, and relationship to other building remains. Artifacts were saved on a sporadic basis, and were only rarely used to aid in the determination of building function and dating.

Knight's excavation on the Barraud lot uncovered the remains of a kitchen, two wells, a smokehouse, three privies, several forge foundations, and numerous landscape features including walkways, and a system of box and gutter drains. These structures and features dated to more than one building period for the lot, and only those believed to be associated with the Dr. Barraud period were later reconstructed by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

2 Figure 1. 18th-century structures associated with the Barraud lot (from Foss 1977:after 10).

Figure 1. 18th-century structures associated with the Barraud lot (from Foss 1977:after 10).

The structures and features were divided into early and later construction periods. Those features dating to the earliest period of occupation on the lot were found to be associated with James Anderson, the blacksmith who purchased the back half of the property in 1767. These features included an industrial related structure consisting of two forges and an associated lean-to, Outbuilding K, a well, and Privy D (Figure 1). Anderson owned the property until 1783, and it is believed that he continued to conduct business on this portion of the lot during the Revolutionary War.

The Anderson period well was only excavated to a depth of ten feet in 1941, due to danger presented by the collapsed well lining. The archaeological report states that "the debris from this well hole was composed mostly of bricks, shell mortar and black earth mixed with a few fragments of eighteenth century china, broken ale bottles and scrap iron" (Knight 1941) . It is possible that the well was filled with debris from Anderson's forge operation after the interior lining of the well collapsed.

The house, kitchen and accompanying drains and walks dated to a later period, with at least the house constructed by the time Dr. Barraud made this half lot his residence in 1783. The remainder of the features, which included a privy, smokehouse, marl walkways, and another well dated from the mid- to late 19th centuries. Using the results of the 1941 excavation, the kitchen, smokehouse and 18th-century well were reconstructed, and the house restored to its colonial appearance.

1987 Archaeological Investigations

In the early fall of 1987, salvage archaeological investigations were undertaken by the Department of Archaeological Research in conjunction with the proposed renovation of the Dr. Barraud property. Only those areas north of the house which were to be disturbed by trenching activities were examined, but these areas did reveal a great deal of information about the property.

Unlike the Knight cross-trenching, which focused on locating structures, techniques used by the Department of Archaeological Research consist of excavating the soil in levels determined by color and texture changes. These natural and man-made soil layers reveal information about the use of the property during different time periods, and allows greater control over dating structures and features through the recovery and analysis of artifacts.

Directly north of the house, a proposed utility trench leading from the Barraud House north towards the kitchen was to cut through and destroy the foundations of two structures labeled during the 1941 excavations as Privy D and the lean-to. Since both of these structures were associated with James Anderson's ownership of the property, it was deemed important to gather any information which could be obtained from further archaeological excavation in this area. Of particular interest was Privy D, since a primary characteristic of privies is that they usually contain underground pits, often back-filled with large quantities of household garbage. Such household garbage can often provide dietary and economic information on the household. Since Knight's maps and notes did not mention a pit feature within the foundations of Privy D, the trenching at Barraud was expected to cut through just such a feature associated with this privy.

4The excavation in the privy area revealed the brick foundation as it was mapped in 1941 by James Knight. Absent, however, was the back-filled pit feature normally associated with privies. It is possible that the function of this structure was misinterpreted by Knight in 1941.

Trenching through the lean-to cut the structure's foundation walls, but did not reveal any other areas of archaeological interest. Work in other areas of the yard, however, soon revealed features of interest.

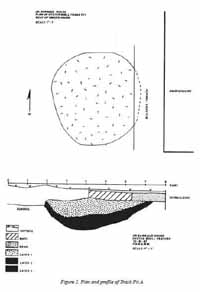

Trash Pit A

The excavation of a well water line running north-south along the west side of the house to the smokehouse at the northern perimeter of the property revealed a late 18th-century trash pit (Figure 2). This pit, which was circular and 5' in diameter, contained three distinct layers of fill. Although it had been cut by a James Knight excavation trench from 1941, it was otherwise intact, and contained large amount of household garbage from Dr. Barraud's ownership of the property. The trash pit had obviously been filled by household activity, since, in addition to the items associated with the daily running of a household, the soil layers were indicative of domestic activity. Some of the soil was a very dark organic fill, usually associated with the decay of food remains, while ash from the house or kitchen fires was also present. The thousands of oyster shells found within the pit also attests to the household-related nature of this feature.

Analysis of the ceramics and glass from the trash pit reveal clues about Dr. Barraud's household. Fragments of 67 ceramic vessels and 6 glass vessels were recovered. The ceramics were heavily weighted towards expensive tablewares, with half of the vessels comprised of creamware or pearlware, and over a third were Chinese porcelain. Analysis of the vessel forms showed that food serving and tableware vessel forms (plates, soup plates, tureens, and platters) made up 72% of all vessel forms, with teawares (teacups, saucers, and teapots) making up an additional 16%. The less expensive, coarser bodied food preparation and storage vessels comprised only 2% of the assemblage, thus indicating that the garbage was being generated within the household of the Barraud house and not in the kitchen. A matching set of Chinese porcelain dinner and soup plates contained within the trash pit fill probably represent Dr. Barraud's fine tableware.

Trash Pit B

A second trash pit, located inside the reconstructed smokehouse, was also examined. Only a small portion of this trash deposit was removed by the archaeologists in 1987, but on the basis of this work, the feature appeared to be a rectangular pit measuring 5.5' long from north to south. Its east-west measurements were undetermined, since some of this trash pit had been cut and partially destroyed along its eastern edge by a modern utility trench.

The trash pit contained debris from Anderson's forging operations, mixed with ash and a brown sandy loam. Unlike Barraud's trash pit, which contained large quantities of household garbage, Anderson's trash pit reflected his more industrial use of the property.

5 Figure 2. Plan and profile of Trash Pit A.

Figure 2. Plan and profile of Trash Pit A.

Fragments of only seven ceramic vessels and three wine bottles were represented in the fill. A soup plate, bowl, and patty pan of creamware, a ceramic type available in Virginia after 1769, indicates that the trash pit was filled after that date.

The brief examination of the Barraud lot in 1987 indicates that, despite the structures revealed in the 1941 excavation, a great deal of information still remains intact on this property. Through the use of current excavation techniques, information on yard use, fence lines, garden areas, trash disposal practices, and the material possessions of the property's inhabitants could be revealed.

Bibliography

- Derry, Linda

n.d.Colonial Lot 19; Brick House and Barraud. Archaeology Briefing. Manuscript prepared for the Department of Archaeological Research, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. - Foss, Robert

1977Report on the 1975 Archaeological Excavations at the James Anderson House. Report on file, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. - Knight, James

1942Archaeological Report, Block 10, Area F, Ryland Lot. Unpublished report on file at the Research Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.